In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

The black gay romance novel emerges in the mid-1980s both as a riffing response to the kind of pop heteronorm performed by mass mediated hip hop, as well as to the consolidated white gay rights agenda, the rising homonorm that aims to exclude black man-on-man desire while claiming that its own articulation of same-sexuality is categorical, universal, and biologically ordained. (676)

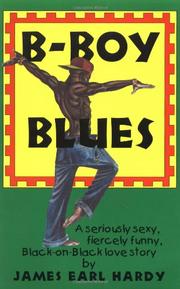

He focuses on Larry Duplechan's Eight Days a Week (1985), James Earl Hardy's B-Boy Blues (1994) and E. Lynn Harris's Invisible Life (1994).

Ross is critical of "hegemonic, homonormal modes of identification that fix gender-dissident desire in order to legitimate it on par with heterosexual love" (674) and while the novels he's chosen are definitely about romantic relationships, I'm not sure they're strictly speaking "romance novels" as defined by the Romance Writers of America, who stipulate that there should be:

A Central Love Story: The main plot centers around individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work. A writer can include as many subplots as he/she wants as long as the love story is the main focus of the novel.

An Emotionally-Satisfying and Optimistic Ending: In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.

Larry Duplechan's novel was

aimed at the new gay white culture forming in the ghettoes of the urban North. The story of an aspiring twenty-two-year-old black gay singer who falls in love with a blond bisexual ex-football player, Duplechan’s first novel, like his succeeding ones, might be called integrationist fantasies, like the post-Civil Rights narratives of good noble blacks, usually men, single-handedly integrating white institutions. (678)

There is apparently no happy ending for the central couple because, "despite their fierce attraction to each other, their relationship fails" (Nelson 633).

Hardy and Harris's books are both the first installment in series. I have the impression that Hardy's comes closest to the pattern expected of "romances" because

Hardy clings to one signal attribute of homonormative romance, the rule that true love can be manifested only in the heteronormalizing coupling convention, as Ann duCille labels this trend in African American women’s fiction. In addition to ruffneck Pooquie’s eventual self-acceptance as a man-loving man who can take it up the ass with the best of sissy-punks, many of Littlebit’s and Pooquie’s love trials revolve around sexual fidelity not only to each other but more crucially to the ideal of monandrous commitment. (Ross 680)

The relationship begun in B-Boy Blues evidently has its ups and downs since the sixth book, A House is not a Home (2005) begins "ten years since Mitchell and Raheim became lovers, and four since they broke up" (Kirkus). It would seem to conclude with a "happy for now": "They give their relationship a second chance, but not until the last few pages of the book. Whether it'll work or not, who knows" (Grey853).

I haven't been able to find out exactly what happens to the protagonist of Harris's Invisible Life but his relationships are turbulent and over the course of the series he shares the stage with other couples.

Regardless of whether or not one thinks of these three novels as "romance" or "romantic fiction" they're an important part of the history of black and gay romance novels.

----

Nelson, Emmanuel S. "Duplechan, Larry." The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Multiethnic American Literature: D-H. Ed. Emmanuel S. Nelson. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2005. 632-34.

Romance Writers of America. "About the Romance Genre."

Ross, Marlon B. " 'What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?': Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel." Callaloo 36.3 (2013): 669-687.