Words Will Never Hurt Me?

Stephanie Burley, writing about popular romance fiction, asked her readers

to make a theoretical leap of faith based on two premises. The first is that the language of whiteness and blackness, light and dark, constructs the way readers imagine the fictional bodies populating these texts. The second is that this representational spectrum is indeed connected to our everday experience of actual bodies and the racial schemas that condition our understandings of those bodies. This color imagery invokes traditional racial taxonomies and their ideological investments in the erotic possibilities of light and dark skin. (326)

If that sounds fanciful, perhaps the reader would like to consider Lakoff and Johnson's research, in which they argue that although

metaphor is typically viewed as characteristic of language alone, a matter of words rather than thought or action. [...] We have found, on the contrary, that metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and action. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature. [...] Our concepts structure what we perceive, how we get around in the world, and how we relate to other people. (Lakoff and Johnson 3)

So, I was doubly perturbed to learn about "Dark Romance":

Forced seductions popped up fairly often in the historical romance novels published in the 1980s, wherein a lecherous duke or stable boy driven mad with wild lust would overpower a heroine and ignore her (ambivalent) protestations. Unadulterated rape fantasy, all but absent from romance paperbacks through the ‘90s, eventually came back to life through discreet self-publishing and has continued to gain momentum through online sales.

Currently, the taboo genre is thriving online under the banner of Dark Romance, which takes the rape fantasy even further by removing consent and kink. Books like Prisoner and Consequences are straightforward depictions of men taking women hostage and raping them; eventually falling in love with them, and then living happily ever after with their former victim. (Vargas-Cooper)

First of all, I'm finding it difficult to see how this really fits the definition of a romance novel in anything other than a technical sense. It seems to me much more like erotica with a tacked on happy ending. After all, the RWA definition of romance involves:

A Central Love Story: The main plot centers around individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work. A writer can include as many subplots as he/she wants as long as the love story is the main focus of the novel.

An Emotionally Satisfying and Optimistic Ending: In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.

That's not:

A Central Rape Story which centres around one individual forcing themselves sexually on another, who struggles to escape. The writer can include as many violations as he/she wants as long as the rape is ultimately legitimated by the victim's emotional capitulation.

An Emotionally Implausible Ending (unless you factor in Stockholm Syndrome): In a romance, the rapist who risks their victim's mental and physical wellbeing is rewarded with unconditional love.

And yes, perhaps the combination of the two was common in large numbers of romance novels in the past but I wouldn't have liked to read about it in the days of the "bodice-ripper" and I don't want to read about it now.

To get back to where I started, though, I'm also troubled that this is being called "Dark Romance" because I can't help thinking that in the past an association between darkness and rape led to the creation of

the figure of the "black beast rapist." In response to the mere rumor of such an outrage against a white woman, white men formed lynch mobs. They killed hundreds of Black men during the 1890s. (Martin 141)

The association, and the killing continued:

Make any list of anti-black terrorism in the United States, and you’ll also have a list of attacks justified by the specter of black rape. The Tulsa race riot of 1921—when white Oklahomans burned and bombed a prosperous black section of the city—began after a black teenager was accused of attacking, and perhaps raping, a white girl in an elevator. The Rosewood massacre of 1923, in Florida, was also sparked by an accusation of rape. And most famously, 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered after allegedly making sexual advances on a local white woman. (Bouie)

And on 17 June 2015

A white supremacist gunman told his black victims "you rape our women and you’re taking over our country" as he massacred nine people inside a historic African-American church in the southern city of Charleston. (Sanchez and Foster)

Words matter. They shape how people think, often in a subconscious way. Instead of falling back on euphemistic language which has the consequence of reinforcing damaging associations between darkness, violence and rape, why not just call a romance with a central rape story a "rape romance"? And while we're on the topic, can someone come up with alternatives to "dark secrets" "blackhearted", accident "blackspots", "black marks" and the phrase which suggests it's a good thing to be "not as black as one is painted"?

----

Bouie, Jamelle. "The Deadly History of 'They're Raping Our Women'." Slate. 18 June 2015.

Burley, Stephanie. “Shadows & Silhouettes: The Racial Politics of Category Romance”. Paradoxa 5.13–14 (2000): 324–43.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. 1980. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2003.

Martin, Joel W. “‘My Grandmother Was a Cherokee Princess’: Representations of Indians in Southern History”. Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture. Ed. S. Elizabeth Bird. Boulder, Colorado: Westview, 1998. 129–47.

Romance Writers of America. "About The Romance Genre."

Sanchez, Raf and Peter Foster. "'You rape our women and are taking over our country,' Charleston church gunman told black victims." The Telegraph. 18 June 2015.

Vargas-Cooper, Natasha. "My Hot, Consensual Introduction to the Rape Fantasy Romance Novel." Jezebel. 19 May 2015.

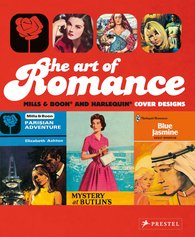

I also noticed that although An is focussed on the cover art of category romances, she doesn't mention Joanna Bowring and Margaret O'Brien's

I also noticed that although An is focussed on the cover art of category romances, she doesn't mention Joanna Bowring and Margaret O'Brien's