Quick Quotes: The Pursuit of Happiness

I'll leave you to draw your own conclusions. I just thought these quotes were thought-provoking when juxtaposed.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. (US Declaration of Independence, 1776)

pursuit of pleasure towards the goal of happiness became seen amongst Enlightenment writers as the behaviour dictated to man by Nature. 'Pleasure is now, and ought to be, your business,' Chesterfield told his son. The tendency to produce happiness was the only ultimate yardstick of right and wrong, good and evil.

If Nature was good, then erotic desire, far from being sinful, itself became desirable. And the sexual instincts were undoubtedly natural. Being pleasure-giving, such passions were thus to be approved. [...] These naturalistic and hedonistic assumptions - that Nature had made men to follow pleasure, that sex was pleasurable, and that it was natural to follow one's amorous urges - informed Enlightenment attitudes towards sexuality. (Parker and Hall, 19)

Although there is no consensus about the exact span of time that corresponds to the American Enlightenment, it is safe to say that it occurred during the eighteenth century among thinkers in British North America and the early United States and was inspired by the ideas of the British and French Enlightenments. Based on the metaphor of bringing light to the Dark Age, the Age of the Enlightenment (Siècle des lumières in French and Aufklärung in German) shifted allegiances away from absolute authority, whether religious or political, to more skeptical and optimistic attitudes about human nature, religion and politics. In the American context, thinkers such as Thomas Paine, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin invented and adopted revolutionary ideas about scientific rationality, religious toleration and experimental political organization—ideas that would have far-reaching effects on the development of the fledgling nation. (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, emphasis added)

Founding fathers (act. 1765–1836) [...] At a minimum the roster includes the seven figures identified in 1973 by Richard B. Morris, the eminent historian of the revolution: Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, links and emphasis added)

--------

Porter, Roy & Lesley Hall. The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995.

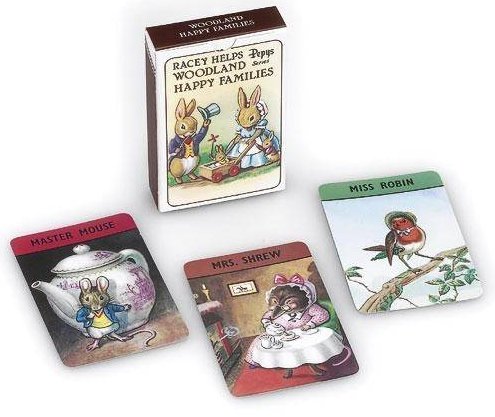

The image came from Amazon. The underpants are not currently available for sale.