American War and Peace

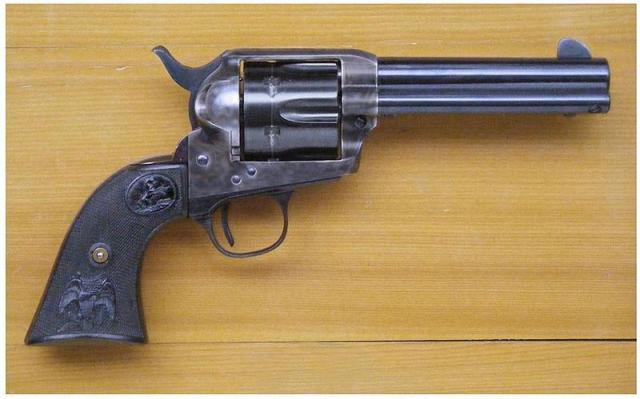

"The good people in this world are very far from being satisfied with each other and my arms are the best peacemaker" - Samuel Colt

It has been argued that novels "are stories, narratives of culture, history, and our collective dreams of the future" (Spurgeon 4) and

From the end of the seventeenth century when early tales of Indian wars and captivity were among the first best-sellers, through the nineteenth-century fascination with bloody sagas of the western frontier and gothic thrillers about the cities, down to the violent gunfighters, private eyes, gangsters and gangbusters of twentieth-century film and television, the American public has made its legends of violence a primary article of domestic consumption, and of export. So potent and pervasive have been these American images of violence that it is through them that Americans have been imaginatively known to much of the rest of the world.

One puzzling thing is that, in spite of this penchant for imagined violence, Americans have traditionally thought of themselves as a nonviolent law-abiding people. Our rhetoric of manifest destiny in the nineteenth century taught that America was the great redeemer nation bringing peace, democracy, and the rule of law to all the world. Though much of this rhetoric is obsolescent and even seems, to some, obscene, the basic belief in America's role as a peace-bringer still retains its hold. (Cawelti 524)

Cawelti concludes that "Americans have a deep belief in the moral necessity of violence and that this belief accounts for the paradox of an ostensibly peace-loving and lawful people being so obsessed with violence" (525).

In a cultural context in which a peace-bringing nation is expected to resort to moral violence, it is perhaps not so surprising that a "pacifist" may be defined not as "a person who believes that war and violence are unjustifiable" (Oxford Dictionaries) but as someone who believes that they are justifiable in certain circumstances. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes that, "Oddly enough, the term pacifism has occasionally been used to describe a pragmatic commitment to using war to create peace" and this kind of pacifism is

known as contingent pacifism. While absolute pacifism admits no exceptions to the rejection of war and violence, contingent pacifism is usually understood as a principled rejection of a particular war. A different version of contingent pacifism can also be understood to hold that pacifism is only an obligation for a particular group of individuals and not for everyone. Contingent pacifism can also be a principled rejection of a particular military system or set of military policies. Contingent pacifists may accept the permissibility or even necessity of war in some circumstances and reject it in others, while absolute pacifists will always and everywhere reject war and violence. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosphy)

Suzanne Brockmann is a romance author who is well known for writing about heroes (and plenty of heroines too) who are trained in the use of violence and I therefore suspect that when she calls herself a "pacifist" she means that to indicate a commitment to contingent rather than absolute pacifism. She has said that

I've always been — starting from back around when, I guess I was around 11, I became a World War II history buff, and so I'm fascinated by military history. I have an incredible respect for the servicemen and women who serve our country. I knew the research was going to be fascinating, and it said in this article at the time there were something like 2,874 active duty Navy SEALs in the Navy today, and I thought, “And I'll write a book for every one of them.

As somebody who has an incredible respect for people who will not quit, for people who have that incredible drive and incredible motivation and incredible willpower, I really felt like it was a really good match for me as a writer. And I'm also a pacifist. And so you combine that with the idea that Navy SEALs are very often used in place of conventional warfare, it just really worked for me. (Popular Romance Project)

Romances which endorse absolute pacifism are extremely rare; it is not uncommon, however, for romances to show the toll which violence takes on soldiers, their families, and other civilians. In an essay about US romances "in which one or both protagonists are combatants in some form of military or political conflict" (153) Jayashree Kamble concludes that

In the symbolic act that is each romance text lie conflicting narratives: on the one side is a systemic conviction in America's mission to protect capitalist democracy, freedom, human rights, and so on, and on the other, the concern that this mission means using good men as cannon fodder and punishing innocents [...]. In other words, warrior romances often contain the awareness that the conflation of concepts such as patriotism toward a civilized nation and the ruthless methods used to display that patriotism is untenable. This awareness shows itself in the text as the threat of the breakdown of the sanity and moral framework of the individuals that make up the nation's army, and also in the devastation it wreaks on family and the alleged foe. The warrior romance thus contains an unmistakable trace of affirmative culture and government-inspired propaganda, such as in its endorsement of America's need to confront the shadowy enemies of abstract noble causes. But it also contains an undercurrent of doubt and despair at the seemingly endless conflict that this engenders. (162)

Perhaps it's because Nora Roberts' First Impressions (1984) isn't a "warrior romance," and because the war under discussion was an internal one which pitted American against American rather than against an external enemy that Shane, her heroine, is able to be quite explicit about a feeling which, in a "warrior romance," might remain only an "undercurrent":

Vance shot her a curious look. "War really fascinates you, doesn't it?"

Shane looked out over the field. "It's the only true obscenity. The only time killing's glorified rather than condemned. Men become statistics. I wonder if there's anything more dehumanizing." Her voice became more thoughtful. "Haven't you ever found it odd that to kill one to one is considered man's ultimate crime, but the more a man kills during war, the more he's honored? [...]" (118)

--------

Cawelti, John G. "Myths of Violence in American Popular Culture." Critical Inquiry 1.3 (1975): 521-541.

Kamble, Jayashree. "Patriotism, Passion, and PTSD: The Critique of War in Popular Romance Fiction." New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction: Critical Essays. Ed. Sarah S. G. Frantz and Eric Murphy Selinger. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012. 153-163.

Popular Romance Project. "Choosing SEALs." 18 December 2012.

Roberts, Nora. First Impressions. 1984. New York: Silhouette, 2008.

Spurgeon, Sara L. Exploding the Western: Myths of Empire on the Postmodern Frontier. College Station: Texas A & M UP, 2005.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Pacifism."

------

The image of the Colt "Peacemaker" came from Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain.

If you've ever wondered why so many romance heroines are (wrongly) identified as "gold-diggers," Stephen Sharot's "Wealth and/or Love: Class and Gender in the Cross-Class Romance Films of the Great Depression" may provide the answer:

If you've ever wondered why so many romance heroines are (wrongly) identified as "gold-diggers," Stephen Sharot's "Wealth and/or Love: Class and Gender in the Cross-Class Romance Films of the Great Depression" may provide the answer: The latest issue of the Journal of Popular Culture came out a few days ago and although none of the articles were directly about romance, quite a few of them have some relevance to it. For example, Kirk Combe begins his article about the "bourgeois rake" in rom-coms by stating that

The latest issue of the Journal of Popular Culture came out a few days ago and although none of the articles were directly about romance, quite a few of them have some relevance to it. For example, Kirk Combe begins his article about the "bourgeois rake" in rom-coms by stating that In "Gender Role Models in Fictional Novels for Emerging Adult Lesbians" Cook, Rostosky and Riggle state that

In "Gender Role Models in Fictional Novels for Emerging Adult Lesbians" Cook, Rostosky and Riggle state that